Lecture 10

MAP, MLE, and Score Function

$$

$$

Gradient Descent with Score Function

The classic inverse problem is defined as

\[b = F(x) + \epsilon\]

where \(F(x)\) is the forward operator, \(b\) is the observed data, and \(\epsilon\) represents the noise in the measurement or process. We often assume that \(\epsilon\) is Gaussian with zero mean and covariance matrix \(\Sigma\).

\[ \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \Sigma) \]

The probability of deviation of the observed data from the forward model in this case is given by: \[ \pi(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{m/2}|\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\epsilon^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} \epsilon\right) \]

Without any prior information about the error, it is difficult to estimate the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). For the purpose of this analysis we can assume that it is a normal distriution with zero mean and a diagonal \(\sigma^2 I\) covariance matrix. The likelihood function simplifies to:

\[ \pi(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{(2\pi \sigma^2)^{m/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\|b-F(x)\|^2 \right) \]

To model the probability distribution of the inverse problem parameters \(x\), we introduce a prior distribution \(\pi(x)\). To ensure positivity of \(\pi(x)\) over the entire domain and proper normalization, we define it using a potential function \(\phi(x, \theta)\): \[\pi(x; \theta) = \frac{e^{-\phi(x, \theta)}}{Z(\theta)}\]

Where the partion function \(Z(\theta)\) is given by:

\[Z(\theta) = \int_\Omega e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} dx\]

Note the partition function is required to make the probability distribution integrate to \(1\). The exponential operator on the potential ensures that all \(\pi(x)\) values are positve since \(e^\phi > 0\) for all \(z \in \mathbb{R}\). In practice, it is often intractable to directly compute the partition function when updating the model parameters \(\theta\) for distributions that are more complex than a Gaussian.

\(\phi(x, \theta): \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) maps \(x\) to a scalar value, and \(\theta\) are the parameters of the model. For example if we are modeling a Gaussian, the parameters might include the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). It has a physical interpretation as an energy of a system, where \(\phi\) values correspond to low probability density regions. For this reason it is often called the energy function in physics-inspired models.

Maximum A Posteriori Estimation

The goal of maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation is to find the most likely \(x\) given the observed data \(b\) and model parameters \(\theta\), maximize the posterior probability \(\pi(x|b; \theta)\):

\[ \begin{align*} \max_x \pi(x|b; \theta) &= \max_x \frac{\pi(b|x; \theta) \pi(x; \theta)}{\pi(b)}\\ \max_x \underbrace{\pi(x|b; \theta)}_{\text{Posterior}} & = \max_x \underbrace{\pi(b|x; \theta)}_{\text{Likelihood}} \underbrace{\pi(x; \theta)}_{\text{Prior}}\\ \end{align*} \]

Since \(\pi(b)\) is independent of \(x\), it does not affect the maximization problem. Substituting the likelihood and prior distributions, we have:

\[ \begin{align*} & = \max_x \frac{1}{(2\pi \sigma^2)^{m/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\|b-F(x)\|^2 \right) \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} \end{align*} \]

The logarithm is a monotonic function, we can maximize the log-likelihood instead of the likelihood with no loss of generality. \(\max_x \pi(x) = \max_x \log(\pi(x))\). Intuitively, since the logarithim is always increasing in output, \(\log(z) > \log(y)\) implies \(z > y\). In addition the product of two exponentials is the same as the sum of the exponents, and the maximum of a function is the same as the minimum of the negative of the function. This allows us to rewrite the log-likelihood as:

We have looked at methods previously of how to differentiate the forward operator \(F\) and perform gradient descent. We take the gradient with respect to \(x\) to find the minimum of the function.

\[ \begin{align*} g &= \nabla_x \left(\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\|b-F(x)\|^2 - \phi(x, \theta)\right)\\ &= \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \frac{\partial F}{\partial x} (F(x) - b) - \nabla_x \phi(x, \theta)\\ &= \frac{1}{\sigma^2} J^T(x) (F(x) - b) + s(x, \theta) \end{align*} \]

Using gradient descent, we can update the model parameters \(\theta\) by taking steps in away from the direction of the gradient \(g\):

\[x_{k+1} = x_k - \alpha g\]

Score Function

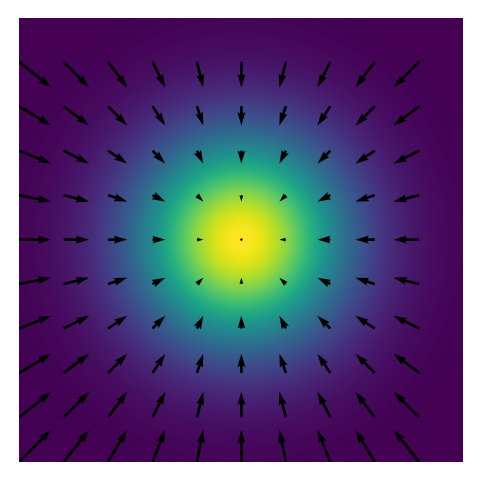

\(s(x;\theta)\) is known as the score function of \(\pi(x; theta)\). \[s(x, \theta):= \nabla_x \log (\pi(x)) = - \nabla_x \phi(x, \theta) + C\]

It is the negative gradient of the potential function \(\phi(x, \theta)\) with respect to \(x\). The score function is a generalization of the gradient of the log-likelihood function, and is described in more detail in Schervish’s “Theory of Statistics” (Schervish 1995).

Score has a physical intution connected to energy potentials and fields. In physics, the electric field \(\mathbf{E}\) is the negative gradient of the electric potential \(V\): \[ \mathbf{E} = -\nabla_x V(x)\]

Simalarly, the score function is the negative gradient of the potential function \(\phi(x, \theta)\) in the case where \(\pi(x) = e^{-\phi(x, \theta)}\). The score function is the direction in which the probability distribution is most likely to change.

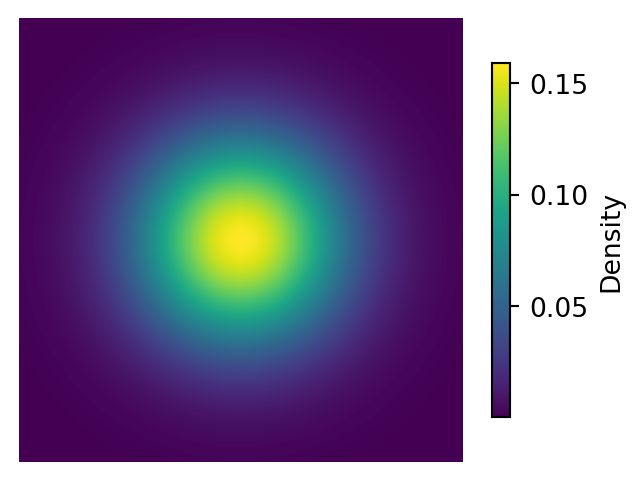

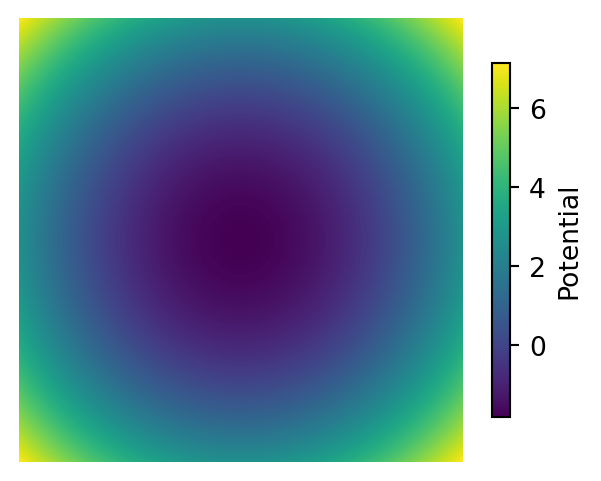

Example: 2D Gaussian Distribution

Consider a 2D Gaussian distribution with zero mean and covariance \(\sigma^2 I\):

| Function | Expression |

|---|---|

| Probability Distribution | \(\pi(x) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sigma^2}\exp\left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \| x \|^2 \right)\) |

| Potential Function | \(\phi(x, \theta) = - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \| x \|^2 - \log(2\pi \sigma^2)\) |

| Score Function | \(-\nabla_x \phi(x, \theta) = -\left( -\frac{x}{\sigma^2} x \right) = \frac{x}{\sigma^2}\) |

In regions of high probability density, the potential function is low becuase the relation \(\pi(x) = e^{-\phi(x, \theta)}\) is monotonic in \(\phi(x, \theta)\). The score funtion is always pointing in the local direction of the largest directional derivative of the probability distribution \(\pi\).

Visualization

Below is a visualization of the probability density function (PDF), potential function, and score function of a 2D Gaussian distribution.

Show the code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Make plots for a 2D Gaussian distribution heatmap, potential function, and score function

# Define the 2D Gaussian distribution

def gaussian_pdf(x, y, sigma=1):

return np.exp(-0.5*(x**2 + y**2)/sigma**2)/(2*np.pi*sigma**2)

# Define the potential function

def potential_function(x, y, sigma=1):

return 0.5*(x**2 + y**2)/sigma**2 - np.log(2*np.pi*sigma**2)

# Define the score function

def score_function(x, y, sigma=1):

return -np.array([x, y])/sigma**2

# Create a grid of points

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

y = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

# Compute the PDF, potential function, and score function

pdf = gaussian_pdf(X, Y)

potential = potential_function(X, Y)

score = score_function(X, Y)

# Plot the Probability Distribution with a colorbar

plt.figure(figsize=(4, 3))

im = plt.imshow(pdf, cmap='viridis', extent=[-3, 3, -3, 3])

plt.axis('off')

plt.colorbar(im, shrink=0.8, label="Density")

plt.show()

# Plot the Potential Function with a colorbar

plt.figure(figsize=(4, 3))

im = plt.imshow(potential, cmap='viridis', extent=[-3, 3, -3, 3])

plt.axis('off')

plt.colorbar(im, shrink=0.8, label="Potential")

plt.show()

# Downsample the grid for quiver plotting

step = 50 # Downsample by taking every 50th point

X_downsampled = X[::step, ::step]

Y_downsampled = Y[::step, ::step]

score_downsampled = score_function(X_downsampled, Y_downsampled)

# Plot the Score Function as a quiver plot over the PDF

plt.figure(figsize=(4, 3))

plt.imshow(pdf, cmap='viridis', extent=[-3, 3, -3, 3])

plt.quiver(

X_downsampled, Y_downsampled,

score_downsampled[0], score_downsampled[1],

color='black'

)

plt.axis('off')

# Save to file

plt.savefig("imgs/score_function.png", bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Maximum Likelihood Estimate from Samples

A common problem is estimating a probability distribution \(\pi(x)\) based on a set of empirical samples \(\{x_1, x_2, ..., x_N\}\). Often in statistical analysis, we are working with an unknown \(\pi\) and attempting to make our best estimate from sampled data. If we assume that the drawn samples are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), then the likelihood of the samples is the product of the likelihood of each sample. Recalling that \(Z(\theta) = \int_\Omega \pi(x) dx\), the likelihood of the samples is:

\[ \begin{align*} \pi(x_1, x_2, ..., x_N) &= \prod_{i=1}^N \pi(x_i) = \pi(x_1) \pi(x_2) ... \pi(x_N) \\ &= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp\left(-\phi(x_1, \theta)\right) \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp\left(-\phi(x_2, \theta)\right) ... \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp\left(-\phi(x_N, \theta)\right) \\ &= \frac{1}{\left[Z(\theta)\right]^N} \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^N \phi(x_i, \theta)\right) \end{align*} \]

Since some \(x\) are observed, the challenge is to find the potential function \(\phi(x, \theta)\) that maximizes the likelihood of the samples, given the model parameters \(\theta\) and a fixed family of \(\phi(,;\theta)\) functions.

The Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) is the process of finding the parameters \(\theta\) that maximize the likelihood of having observed the samples. Unlike the MAP estimate, there is no posterior and prior distribution. So in this case \(\pi(x|\theta)\) is being directly maximized. This is equivalent to minimizing the negative log-likelihood as before:

\[ \begin{align*} \text{MLE} &= \text{argmax}_\theta \frac{1}{\left[Z(\theta)\right]^N} \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^N \phi(x_i, \theta)\right)\\ &= \operatorname*{argmin}_\theta N \log(Z(\theta)) + \sum_{i=1}^N \phi(x_i, \theta)\\ &= \operatorname*{argmin}_\theta \log(Z(\theta)) + \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \phi(x_i, \theta) \end{align*} \]

However we again run into the problem of the partition function \(Z(\theta)\) which for most distributions in higher dimensions is intractable to compute. For example we may be trying to solve an integral in \(100\) dimensions with no analytical solution.

\[ \int_{x_1} \int_{x_2} ... \int_{x_{100}} e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} dx_1 dx_2 ... dx_{100} \]

Minimizing with Gradient Descent

The gradient of the MLE objective with respect to \(\theta\) is:

\[ \begin{align*} g &= \nabla_\theta \left( \log(Z(\theta)) + \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \phi(x_i, \theta) \right)\\ &= \nabla_\theta \log(Z(\theta)) + \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \nabla_\theta \phi(x_i, \theta) \end{align*} \]

The left side term can be further reduced by using the definition of the partion function \(Z(\theta) = \int_\Omega e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} dx\), the probability distribution \(\pi_\theta(x) = e^{-\phi(x, \theta)}\):

\[ \begin{align*} \nabla_\theta \log(Z(\theta)) &= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)}\nabla_\theta \int_\Omega e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} dx\\ &= \int_\Omega \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \nabla_\theta e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} dx\\ &= - \int_\Omega \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} e^{-\phi(x, \theta)} \nabla_\theta \phi(x, \theta) dx\\ &= - \int_\Omega \pi(x) \nabla_\theta \phi(x, \theta) dx\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{x \sim \pi_\theta(x)} \left[ -\nabla_\theta \phi(x, \theta) \right]\\ & \approxeq \frac{1}{M} \sum_{i=1}^M -\nabla_\theta \phi(x_i, \theta) \end{align*} \]

We estimate the value of \(\nabla_\theta \log(Z(\theta))\) by taking the expectation value of the score function over the samples. This is a Monte Carlo approximation of the true integral using the available i.i.d. samples \(\{ x_1, x_2, ..., x_N \}\). The gradient of the MLE objective is then:

An optimal point is reached by first order optimality conditions, where the gradient is zero. The MLE objective is minimized when the synthesis and analysis terms are equal. This is known as score matching and is a method for estimating the parameters of a probability distribution from samples. The synthesis \(\tilde x_i\) terms are drawn randomly from the proposed score \(\phi(\tilde x_i, \theta)\) , while the analysis \(x_i\) terms are taken over the samples \(\{x_1, x_2, ..., x_N\}\).

As before gradient descent can be used to update the model parameters \(\theta\):

\[\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k - \alpha g\]

An Application of Score: Langevin Dynamics

An example of the usage of a learned score function is in Langevin Dynamics. Langevin Dynamics is a method for sampling from a probability distribution \(\pi(x)\) by simulating a stochastic differential equation (SDE) that converges to the distribution. The SDE is given by:

\[dx = -\nabla_x \phi(x, \theta) dt + \sqrt{2} dW\]

The score function pushes samples towards regions of high probability density, since it is a vector that points in the direction of maximum increase of the probability distribution. The noise term \(dW\) is a Wiener process, which is a continuous-time stochastic process that is normally distributed with mean zero and variance \(dt\). The Langevin Dynamics algorithm is a discretized version of the SDE:

\[x_{k+1} = x_k - \underbrace{\Delta t \nabla_x \phi(x_k, \theta)}_\text{Score Term} + \underbrace{\sqrt{2 \Delta t} z_k}_\text{Stochastic Term}\]

Where \(z_k \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) is a random sample from a normal distribution with zero mean and unit variance.

The score points in the same direciton as the gradient of the probability distribution, so at each time step, the score term moves the sample to a higher probability region. The stochastic term adds noise to the sample, providing randomness to the process.

Code Example

Below is an example of Langevin Dynamics applied to a 2D Gaussian distribution. The score function is used to push the samples towards the center of the distribution, while the stochastic element adds noise and randomization to the process. The animation show an intial uniform sampling grid of points converging to the shape of the Gaussian distribution.

Show the code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

import seaborn as sns

# Ensure the Pillow writer is available

from matplotlib.animation import PillowWriter

# Define the 2D Gaussian distribution

def gaussian_pdf(x, y, sigma=1):

return np.exp(-0.5*(x**2 + y**2)/sigma**2)/(2*np.pi*sigma**2)

# Define the potential function

def potential_function(x, y, sigma=1):

return 0.5*(x**2 + y**2)/sigma**2 - np.log(2*np.pi*sigma**2)

# Define the score function

def score_function(x, y, sigma=1):

return -np.array([x, y])/sigma**2

# Define the Langevin Dynamics update

def langevin_dynamics(samples, sigma=1, dt=0.05):

z = np.random.normal(0, 1, samples.shape)

score = score_function(samples[:, 0], samples[:, 1], sigma)

samples = samples + dt * score.T + np.sqrt(2 * dt) * z

return samples

# Create a grid of points for the contour plot

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

y = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

# Compute the PDF for contour plotting

sigma = .5

pdf = gaussian_pdf(X, Y, sigma)

# Initialize samples on a 5x5 grid

grid_size = 10

grid_range = np.linspace(-2.5, 2.5, grid_size)

initial_samples = np.array([[x, y] for x in grid_range for y in grid_range])

samples = initial_samples.copy()

# Set up the figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

# Plot the initial contour

contour = ax.contourf(X, Y, pdf, levels=50, cmap='viridis')

scatter = ax.scatter(samples[:, 0], samples[:, 1], color='red', s=30, label='Samples')

# Add a legend

ax.legend()

# Function to update the animation at each frame

def update(frame):

global samples

samples = langevin_dynamics(samples, dt=0.002, sigma=sigma)

scatter.set_offsets(samples)

ax.set_title(f'Langevin Dynamics Iteration: {frame+1}')

return scatter,

# Create the animation

ani = animation.FuncAnimation(

fig, update, frames=400, interval=200, blit=True, repeat=False

)

# Save the animation as a GIF

ani.save("imgs/langevin_dynamics.gif", writer="imagemagick", fps=10)

# Display the animation inline (if supported)

plt.close(fig)MAP Estimation with General Gaussian

Revisitng the MAP estimation problem, we can consider a more general prior \(\pi(x)\) with mean \(\mu = 0\) and covariance \(\Sigma\):

\[ \begin{align*} \pi(b|x) &= \frac{1}{(2\pi \sigma^2)^{m/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\|b-F(x)\|^2 \right)\\ \pi_\theta(x) &= \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{n/2}|\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}x^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x\right)\\ \text{MAP} &= \min_x \left( \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\|b-F(x)\|^2 + \frac{1}{2}x^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x \right) \end{align*} \]

We now make a choice of which \(pi_\theta(x)\) to use, as before this is a MLE based on the available empirical samples. For the purpose of finding the gradient, let the minimization parameters be \(\theta = \Sigma^{-1}\), since the true \(\Sigma\) is positive definite, it can be found by inverting this result. The partition function \(Z(\theta)\) is known for the case of a Gaussian distribution, and so the MLE objective is:

\[ \begin{align*} \pi(x) &= \max_\theta \Pi_{i=1}^N \pi_\theta(x_i)\\ &= \max_\theta \frac{1}{Z(\theta)^N} \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^N \frac{1}{2}x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i\right)\\ &= \min_\theta N \log(Z(\theta)) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i\\ &= \min_\theta -\log((2\pi)^{n/2}|\Sigma|^{1/2}) + \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i\\ &= \min_\theta -\frac{1}{2}\log(|\Sigma|) + \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i \end{align*} \]

Finding the Gradient

Left Term: To find the min using gradient descent we take the gradient of each term with respect to \(\Sigma^{-1}\). The gradient of a log determinant can be found in the matrix cookbook (Petersen and Pedersen 2012) formula (57): \[ \nabla_{A} \log(|A|) = (A^{-1})^\intercal \]

This can be rewritten as:

\[ \nabla_A \log(|A^{-1}|) = A^\intercal\]

Applying this to the left term we get:

\[ \nabla_{\Sigma^{-1}} \left( -\frac{1}{2}\log(|\Sigma|) \right) = -\frac{1}{2} \Sigma\]

Right Term: The gradient of the second term is found by reformulating it as a trace of a new matrix \(X = \sum x_i x_i^\intercal\):

\[ \begin{align*} \sum x_j^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_j &= \sum \text{trace} \left( x_j^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_j \right)\\ &= \sum \text{trace} \left( \Sigma^{-1} x_j x_j^\intercal \right)\\ &= \text{trace} \left( \Sigma^{-1} X\right)\\ \end{align*} \]

The matrix cookbook (Petersen and Pedersen 2012) formula (100) gives the gradient of the trace of a matrix product:

\[ \nabla_X \text{trace}(XB) = B^\intercal\]

Applying this we get:

\[ \nabla_{\Sigma^{-1}} \left( \frac{1}{2N} \sum x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i \right) = \frac{1}{2N} X^\intercal = \frac{1}{2N} \sum x_i x_i^\intercal\]

Combined Result:

Combining the two terms we get the gradient of the MLE objective with respect to \(\Sigma^{-1}\): \[ \begin{align*} g &= \nabla_{\Sigma^{-1}} \left( \frac{1}{2}\log(|\Sigma|^{-1}) + \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x_i \right)\\ &= \frac{1}{2} \Sigma^\intercal - \frac{1}{2N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i x_i^\intercal \end{align*} \]

Solving for where the gradient is zero, we find the optimal value of \(\Sigma\), since \(\Sigma = \Sigma^\intercal\):

\[ \Sigma = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i x_i^\intercal\]

This is the maximum likelihood estimate of the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) given the samples \(\{x_1, x_2, ..., x_N\}\), which can be interpreted as the expectation value of the outer product of the samples. The estimated covariance matrix is the actual true covariance matrix of the sampled data. This is a common result in statistics, where the sample mean is the MLE of the true mean of the distribution.

Unfortunately, estimating parameters can be very difficult to do for non-Gaussian \(\pi_\theta\) due to the partition function \(Z(\theta)\) being intractable.

Conclusion

MAP estimation on an inverse problem may require the use of a prior distribution \(\pi(x)\) to regularize the solution. The potential function \(\phi(x, \theta)\) is used to define the probability distribution \(\pi(x; \theta)\), and the score function \(s(x, \theta)\) is the negative gradient of the potential function.

If the prior is not known, an MLE estimate can be made to find the parameters \(\theta\) that maximize the likelihood of the samples based on an assumed parameterized model. The score matching gradient is used to estimate the gradient of the MLE objective with respect to \(\theta\).